A new study on hamsters reveals that nasal and oral vaccines could effectively stop the transmission of respiratory infections like Covid-19, offering hope for a more targeted approach to pandemic control.

Researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have demonstrated that vaccines administered through the nose and mouth can achieve what conventional injections have only partially accomplished: potentially curbing the spread of Covid-19 by halting virus transmission.

Rise in coronavirus infections

Germany is currently experiencing an unusually high number of respiratory infections. The number of Covid-19 cases reported to the RKI has recently increased slightly in the 29th reporting week compared to the previous week. However, most people in Germany are multiply vaccinated and have already overcome one or more infections. Therefore, severe respiratory infections are currently rare, according to the RKI. Nevertheless, even milder infections can burden those affected and lead to absences from work.

New vaccine acts on mucous membranes

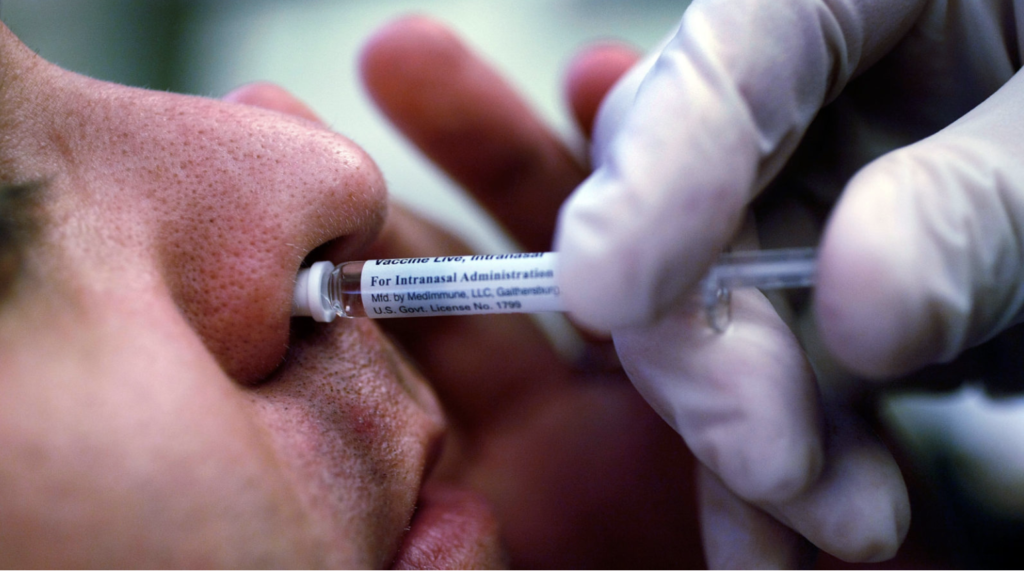

The vaccine developed by researchers at Washington University could make a significant difference. The results, published in the journal “Science Advances,” are promising. While most vaccines are administered into arm or buttock muscles and primarily generate antibodies in the blood, respiratory viruses first infect the mucous membranes in the nose and lungs. Local immunity could therefore be more effective, the researchers hypothesized.

Corona nasal spray already approved in India

Using their nasally administered Covid-19 vaccine “iNCOVACC,” which is already approved in India, the researchers demonstrated that nasally vaccinated hamsters who developed Covid-19 did not transmit the virus to other hamsters, thus breaking the transmission cycle. In contrast, about half of the hamsters in contact with hamsters that received an injection of the Pfizer vaccine became infected.

Furthermore, the data shows that in nasally vaccinated hamsters, the virus content in the respiratory tract was 100 to 100,000 times lower than in those who had received a vaccine injection or were not vaccinated at all.

If vaccines targeting the mucous membranes indeed offer such significant advantages for humans, they could be helpful in the future not only for Covid-19 but also for other diseases – for example, avian influenza, which could increasingly pose a risk to humans in the future. In Finland, risk groups are already being offered vaccination against the virus.